EMV & the Fraud Liability Shift: What It Means for Your Business

You may have noticed that new debit cards and credit cards are being issued with a visible microchip on the front, above the first four digits of the card number. The purpose of the microchip is to make it harder for criminals to use your debit/credit card fraudulently and is designed to meet the EMV standard, which will be discussed in just a moment. However, due to the added security by microchips, issuers of the debit and credit cards have agreed to shift the financial liabilities of card fraud onto merchants starting October 1st, 2015, coining the change as the “fraud liability shift.”

What is EMV?

EMV- which stands for Europay, Mastercard, and Visa- is the global standard for smart cards, and it is the reason why the rules are changing October 1st. Europay, Mastercard, and Visa were the original three payment brands that came together to create the standard. The standard has since been regulated by six payment brands (American Express, Discover, JCB, MasterCard, UnionPay, and Visa) and is now known as EMVCo.

If your business accepts the following cards - Accel, American Express, China UnionPay, Discover, MasterCard, NYCE Payments Network, SHAZAM Network, STAR Network, and Visa - read on to find out how your business will be affected and what you can do to protect your business from the fraud liability shift.

Smart Card vs. Magnetic Strip Card

Unlike traditional debit/credit cards that store data on magnetic strips, smart cards, also referred to as chip cards, store card data on a microchip in the card that produces a random, unique transaction authentication code each time a transaction is made. While the traditional card is swiped to make a transaction, the chip card requires an upgraded machine capable of accepting cards that are inserted as opposed to swiped. Some chip cards can also perform contactless transactions via EMV-compliant POS machines capable of contactless transactions.

Although it has not been formally standardized yet, depending on the financial institution, smart cards may require a PIN or signature at the time of transaction. A smart card requiring a PIN is referred to as “chip-and-PIN” and a smart card requiring a signature is referred to as “chip-and-signature”; chip-and-PIN is more accepted worldwide than Chip & Signature.

Chip cards are also issued with the traditional magnetic strip for backwards compatibility: chip-enabled cards can still be used to make transactions on traditional POS (point-of-sale) machines.

Essentially, the objective of the EMV standard is to reduce counterfeit fraud by setting up a system in which a stolen transaction code cannot be re-used to make other transactions. Of course, it should be noted that the EMV system is not without flaws, and criminals have already committed fraud via loopholes within the system- but more on that in a bit.

What you need to know about the October 1 fraud liability shift

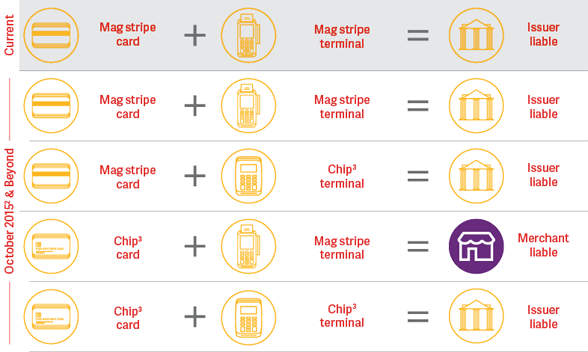

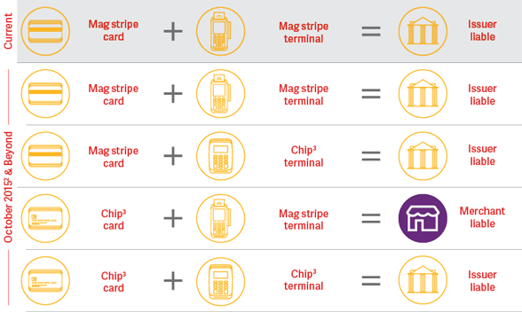

With the change from traditional cards to chip-enabled cards comes a change in regulations defining the party financially responsible for instances of debit/credit card fraud. As the diagram below shows, fraud liability traditionally falls upon the card issuer. However, starting October 1, fraud liability will fall on whichever party has the least EMV-compliant technology. In other words, if a fraudulent transaction is made using a smart card at a traditional POS machine, the merchant is responsible for absorbing the losses from the fraud. If a counterfeit chip card is used at an upgraded, EMV-compliant POS machine, fraud liability will once again fall upon the card issuer.

Visa®, MasterCard®, Discover® and American Express®1

1Same applies for all card brands

2October 2017 for Automated Fuel Dispensers (AFD)

3With or without PIN capabilities

Four things should be noted about the fraud liability shift:

- The arrival of October 1 does not mean that all debit/credit cards need to be EMV compliant, it means that merchants need to be ready to accept chip-enabled cards by that date if they do not want to be affected by the new fraud liability rules.

- Upgrading POS systems to accept chip cards is not legally mandated- it is an optional measure to protect your business from fraud liability.

- Even if you have an updated EMV-compliant POS machine, if you run a counterfeit chip card via the magnetic strip reader instead of the chip reader, you will be liable for the fraud.

- Even if the counterfeit card swiped at a traditional POS machine is in the form of a traditional card, you will be liable for fraud if the data on the counterfeit card was obtained from a legitimate chip card.

Fraud based on lost/stolen cards, as opposed to counterfeited cards, will also have fraud liability shifts that occur on October 1 (American Express, Discover and MasterCard):

Fraud liability shift in the United States

Despite how sudden this shift may seem in the United States, most of the world – Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, the Middle East, Latin America, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia – has already implemented a shift in fraud liability.

The United States is the last major market to adopt the EMV standard and it is not hard to see why: the United States is not only the largest but also the most fragmented of all markets. Add to the fact that the United States is geographically one of the largest markets, as well as the most demographically diverse, in the world.

Until the early 2000’s, the United Kingdom experienced the highest amount of credit card fraud due to the fact that most credit card transactions were batch processed (to cut down on costs) at the end of the business day for verification by the card issuer, which allowed for enough lag time for criminals to get away with fraud. In the United States, verifying credit cards at the time of transaction was much less cost-prohibitive, which significantly reduced lag time, thus reducing that type of fraud. To combat this type of fraud, the United Kingdom eagerly adopted the EMV standard, introducing chip-and-PIN cards in test markets in 2003, and fully adopting the standard nationwide on February 14, 2006.

Since the switch to EMV, the United Kingdom has seen almost a 66% decrease in losses from counterfeit credit cards. But that 66% decrease in UK counterfeit credit card fraud simply meant that criminals took to a new market that better allowed for their fraudulent activities: the United States. Currently, the United States accounts for only 24% of credit card transactions worldwide, but houses 47% of the world’s credit card fraud. To combat this, on October 1, 2015, the United States will finally adopt the EMV standard by shifting fraud liability.

The EMV standard is not perfect

Although it wasn’t until the 21st century that the EMV standard was first officially implemented at POS systems, the concept behind the EMV’s technology is actually over forty years old. The first (and only) patent on the chip card concept was filed in 1970, and it was over twenty years later in 1994 that the original three EMV members first got together to discuss implementation of this technology within a global credit card standard. It took approximately two years to develop a stable enough standard to be adopted worldwide. Since 1996, the standard has only been updated three times; the most recent official revision was back in November 2011, with periodic updates released for specific sections within the most recent revision.

What this all means is that the technology used in EMV-compliant chip cards is based on a concept that is over 40 years old. This, of course, raises the question: is a technology that is decades old able to combat modern, technologically-savvy criminals with access to affordable, sophisticated electronics and materials not available to criminals of yesteryear?

The short answer is: No. There have already been multiple cases of counterfeit chip card fraud around the world, and research by leading universities has put a spotlight on a couple of loopholes in the EMV standard.

In September 2014, Home Depot revealed a massive data breach had compromised about 56 million debit and credit cards. While data breaches are not shocking in this day and age, what was worrisome about this incident was that the card data that was stolen was subsequently used to make fraudulent transactions originating in Brazil that were disguised as legitimate MasterCard and Visa PIN-and-chip cards, even though banks had not yet even issued chip cards. Even more worrisome, it is still a mystery exactly how the criminals managed to make it seem like the fraudulent charges were made on a legitimate chip card, considering that it is quite difficult and costly to make a counterfeit PIN-and-chip card. If cyber criminals managed to figure out how to get past EMV’s security protocols last year, what have they figured out since then?

Cambridge University’s Computer Laboratory published a paper that detailed two holes found in the EMV standard. First, back in 2010, researchers discovered that the “random” authentication code produced by chips at the time of transaction might not be so random after all; as any programmer worth his/her salt will tell you, no machine can generate a truly random number. Terminals, particularly ATMs, are not governed by sophisticated programming and so they generate fairly linear transaction codes, meaning that a criminal with the technical know-how can predict future authentication codes for later use. Researchers demonstrated how this type of fraud can occur even without physically cloning a card, coining this type of fraud as a “pre-play” attack.

Second, in 2014, Cambridge researchers made another discovery: by install malware on a POS machine or an ATM, a fraudster could perform a variation of the pre-play attack by replacing the random number with a number of his/her choosing. This type of fraud could also be perpetrated by a man-in-the-middle between the POS/ATM terminal and the bank that processes transactions.

Also in 2014, Newcastle University published a paper that detailed the ability of Android phones in the UK to perform fraudulent transactions on contactless EMV-compliant Visa chip cards, even while the card is in an unsuspecting card owner’s pocket. By holding the phone close enough to a contactless VISA chip card, a fraudster can approve a foreign currency transaction of up to €999,999.99. Criminals will likely choose a much smaller sum, in the neighborhood of €100-€200 so as not to arouse suspicion. Then, a rogue merchant in one of the 76 countries that accept EMV transactions will take the received fraudulent transactions and transfer money from the transaction from the card owner’s bank to the merchant’s bank using a data conversion process along with a rogue POS machine that is capable of performing the same actions as a legitimate POS machine.

The burden of EMV and the fraud liability shift on small businesses

Although the shift will occur in just a few weeks, experts have estimated that less than 50% of US merchants will be EMV-ready by the October 1st deadline.

Smaller businesses will have a much more difficult time shouldering the financial burden imposed by the EMV standard than big businesses. In a 2015 study published by Intuit (the makers of Quickbooks), 37% of small businesses have not even heard of EMV cards; just about half (52%) of small businesses surveyed stated that they were aware that there is an upcoming fraud liability shift, but only 19% were aware that October 1st is the deadline. Just 42% of small businesses are committed to upgrading their POS systems to be EMV-compliant.

Those who are either unsure or will not be upgrading revealed that the costs of upgrading – the price of new POS machines, the time required to research the machines, the time and resources required to train employees on the new machines, and so on – were the reasons prohibiting them from upgrading their POS systems, even though they admit their business will either probably not be able to or definitely not be able to financially take on the liabilities from card fraud.

In the United States, it has been estimated that merchants will have to spend a total of at least $25 billion to meet EMV standards; Target has already spent about $100 million upgrading their POS system. Each new EMV-compliant POS machine will cost roughly $250, and that price does not include the costs of installation and the costs of training yourself as well as your employees with using these new machines under the EMV protocol. Payment brands and banks have stayed quiet about helping merchants afford the change to EMV-compliant systems. For example, American Express is offering small businesses the grand total of $100 to upgrade their system.

How to prepare your retail business for the fraud liability shift

As a retail business owner, you might be wondering how your business can financially survive the fraud liability shift: upgrading your POS system will cost a great deal of time and money, but not upgrading the system will expose you to fraud liability. What are you to do?

To find out how you can protect your business, read our next post on how to avoid liability after the fraud liability shift.

.png)