Popular culture would have you believe that the Secret Service is an agency whose sole responsibility is providing security to the President of the United States, but they are actually an agency that deals first and foremost with financial crimes – mostly counterfeit money. In fact, the Secret Service was initially created not as a protection detail outfit, but as a method of counterfeit cash suppression.

It is the Secret Service who is called upon whenever counterfeit money turns up. And, if you’re following the news, counterfeit money turns up quite often.

The Prevalence of Counterfeit Money Production

According to the Secret Service, there was approximately $1.36 trillion in U.S. banknotes (bills) in global circulation as of March 11, 2015 and an estimated one quarter of one percent of that amount is counterfeit. This means that there is $3.4 billion in counterfeit U.S. bills currently in circulation. In 2013, the U.S. government discovered and took out nearly $88 million in counterfeit bills from circulation, which, after a little math, is just a fraction of how much counterfeit money is actually in circulation.

Due to its authority and prominence, U.S. money has become the most widely accepted form of currency, with three-quarters of its circulation occurring outside of the United States. Consider Cambodia, where the dollar is “preferred to the domestic Riel currency for high-value transactions such as paying rents and salaries.”

The ubiquity of American currency is what makes counterfeiting quite lucrative on the international level. Counterfeiting is a high-margin $654 billion growth industry, and in Peru (the country that produces the most counterfeit currency), criminals “make more money manufacturing fake currency than they do cocaine.” It is not hard to see why there is so much counterfeit cash in circulation, especially from foreign sources.

Counterfeit Money Fact:“[T]he American $100 bill is one of the most common counterfeit notes on the worldwide market. By contrast, among domestic counterfeiters the most commonly faked bill is the $20.”

– Jennifer Abel, Consumer Affairs

Although there is, of course, domestic counterfeit currency production, it is counterfeit currency emanating from foreign countries that not only make up the bulk of counterfeit U.S. currency, but also, most resembles the look and feel of real currency. There are a couple of reasons why criminals in foreign countries find the counterfeit currency trade so lucrative: first, foreign counterfeiters have access to machinery that domestic counterfeiters do not, and second, foreign counterfeiters are simply able to print more for less than domestic counterfeiters.

In the United States, the type of ink and paper used to print currency are remarkably regulated in order to discourage “offset” printing. Offset printing is the type of printing used by the U.S. Treasury to print money: an inked image of currency is “offset” from a plate to a rubber blanket and onto special paper used for currency. The ink and paper used to print currency are so well regulated that most domestic counterfeit currency is printed via inkjet printing or photocopying, not offset printing.

However, due to the lack of effective law enforcement in certain foreign countries, criminals are able to get their hands on not only the ink and paper used to make real currency, but the type of machinery used to do offset printing as well. After examining a bill that was produced using a machine used to print newspapers and flyers, a U.S. Embassy Secret Service officer remarked, “It’s a very good note.”

“Overseas, it remains a different story. Most of the fake $68.2 million in U.S. currency recovered last fiscal year was churned out by offset presses, the Secret Service says, because these highly efficient “counterfeiting mills” can more easily escape detection by U.S. authorities and even operate with the backing of corrupt governments.”

– Del Quentin Wilber, Bloomberg Business

The access to the ink, paper, and type of machinery used to print currency allows foreign counterfeiters to print sheets upon sheets of fake bills in one sitting; domestic counterfeiters, on the other hand, can only produce fake bills as fast as a printer can print. It is not only the ability to print in bulk that gives foreign counterfeiters a high-margin, but also, the abundance of cheap labor.

Foreign Counterfeit Production > Domestic Counterfeit Production:“In the U.S., counterfeiting tends to be small-bore, almost a cottage industry, involving self-starters using digital technology and producing limited quantities of bills at a time. Operations in Peru continue to use traditional printing techniques, with offset printers — the principal tool of the trade — churning out large numbers of scrip. Nearly all of the major busts have occurred in San Juan de Lurigancho, Lima's largest district (with more than 1 million people), where it is easy to set up shop behind a garage door and go unnoticed. (The capital also has a section where small, legitimate printing presses stretch one after another for blocks, but counterfeiters seem to have avoided — or have not been detected in — that downtown zone.) "Overseas operations tend to be more organized than in the United States. They are using printing presses that allow them to print higher volumes," says Jenkins.”

– Lucien Chauvin, Time

Foreign counterfeit money wouldn’t be so problematic if it weren’t for the fact that much of it makes its way across borders, and eventually circulating back to the United States. In the fall of 2014, Cambodian police seized $7.2 million in counterfeit hundred dollar bills at a border crossing with Thailand, a country in which police had seized $3.7 million in counterfeit bills the previous year. Reiterating just how lucrative foreign counterfeit currency can be: After estimating that it took 2 months to produce the counterfeit $7.2 million, a Special Secret Service agent determined, “You need talented people to do this.”

Domestic Counterfeit Money Usage

Although substantial regulation has affected domestic counterfeiters’ ability to produce realistic fake money through offset printing, that hasn’t stopped them from uncovering various methods of producing counterfeit currency and spending counterfeit currency.

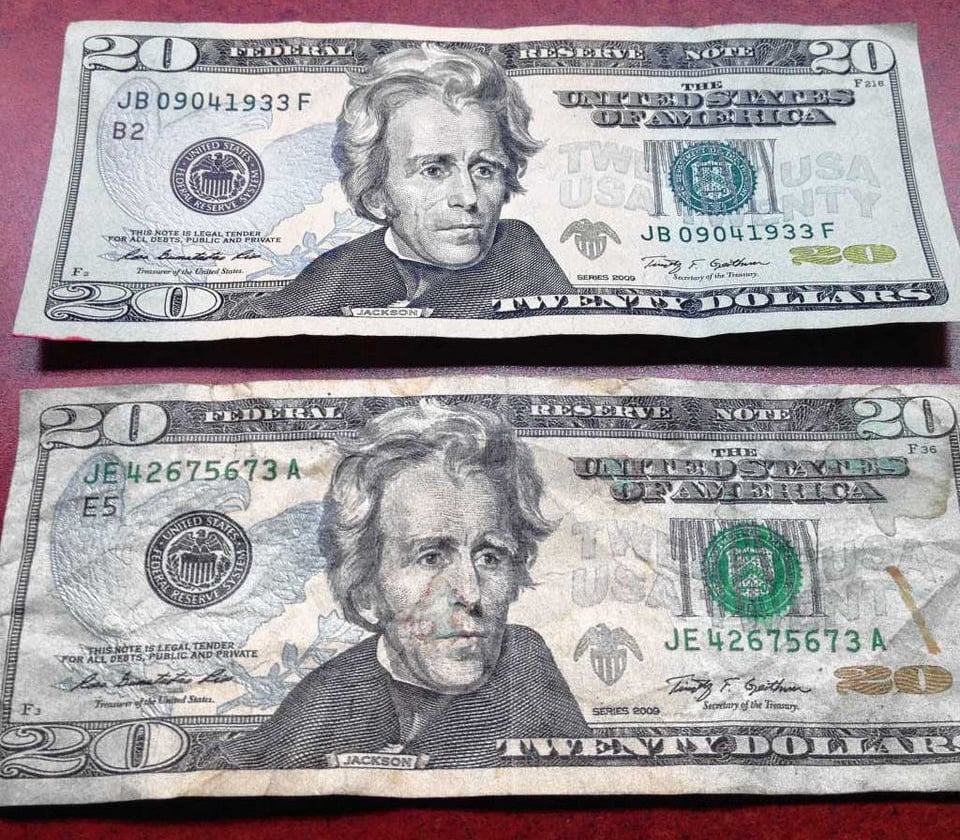

Have you ever come across a fake bill that felt real? That’s probably because it was real at some point. Take for example, the case of Tarshema Brice, a 34-year-old hairstylist and janitor, and mother of six, who produced counterfeit currency to make ends meet. She would soak real $5 bills in a degreaser, scrub off the ink with a toothbrush, dry them with a hairdryer, and reprint them as $50’s and $100’s with an inkjet printer using scanned images of real $50 and $100 bills. At the time she was caught, she estimated that she had printed between $10,000 and $20,000 in counterfeit bills over a period of two years.

Have you ever come across a fake bill that looked as crisp and clean as a real bill? That’s probably because it was proofed by a professional artist. For example, Jean P. Losier, a 39-year-old artist from Palm Beach County, Florida was recently charged with manufacturing more than $4 million in counterfeit bills.

Counterfeit Money Fact:“Last fiscal year, ending Sept. 30, the Secret Service made 3,617 counterfeiting arrests.”

– Bloomberg Business

Although it may go against intuition, counterfeit money usage doesn’t only happen in big cities - with the hustle and bustle of a large consumer population. Counterfeits are spent in rather large amounts in relatively small towns. Consider:

- Springfield, Tennessee, a town with a population of less than 17,000. In just the past two months alone, Springfield police have recovered $1,800 in counterfeit cash.

- Leesburg, Florida, a town with a population of about 20,000. Since January 2015, there have been 63 counterfeit bill cases, but only two arrests.

- Lake Zurich, Illinois, a town with a population of less than 20,000. In just one day, $600 worth of goods was discovered to be purchased with counterfeit cash.

- Eufaula, Alabama, a town with a population of about 13,000. In just one week in November of this year, the police department reported that more than $1,000 in counterfeit cash had been used to purchase goods at several stores

Counterfeit money is, of course, most often spent in larger cities, especially during peak shopping times. As San Francisco’s Gyro Express owner Cem Bulutoglu noted: “Those [counterfeiters] know what they’re doing – they don’t come on slow times, they come when we’re busy.” And criminals know just how busy stores are during the holiday season.

“Counterfeits . . . often go by cashiers when lines of impatient customers are waiting, During the holidays, Secret Service agents see an increase in counterfeiting.”

– Will Kane, SF Gate

During the holidays, stores often find themselves walking the thin line between efficient customer service and effective loss prevention. When lines get long and customers get impatient, cashiers are simply too busy to check each and every bill during a transaction, “especially when someone plops down $700 cash in a mix of real and impressively faked $20 bills.”

The simple fact that there is a large uptick in transactions during the holiday season means that stores can expect a reciprocal uptick in counterfeit cash usage; as Detective Norman Luper of the Greensboro Police Department Fraud and Financial Crimes Division explains: “We see more counterfeit bills during the holiday season since there are more shoppers. More retail traffic means more opportunities for fraudulent bills to be passed.”

Counterfeit Money Fact:“Each week, the local Secret Service office collects $55,000 in fake bills from Northern California banks, and that number is expected to jump before Christmas.”

– Will Kane, SF Gate

Cash is Still King

As noted above, an increase in transactions means a reciprocal increase in counterfeit money usage, signaling a relationship between the use of cash and the use of counterfeit bills. In other words, as long as cash is being used, counterfeit cash will be used as well.

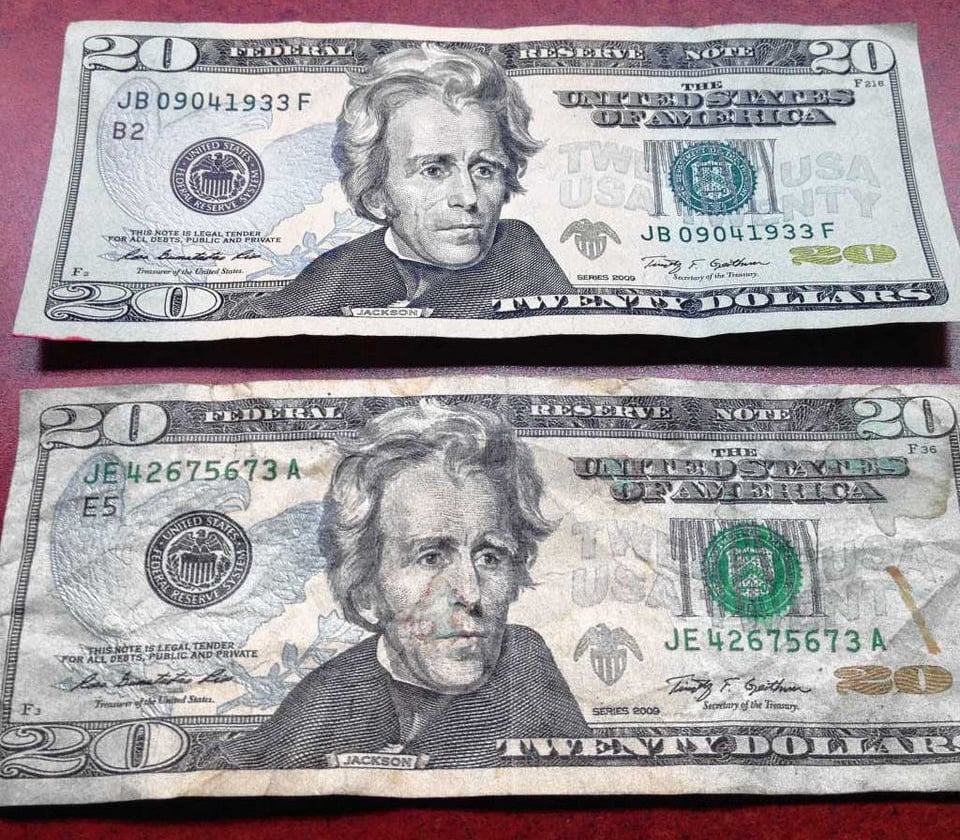

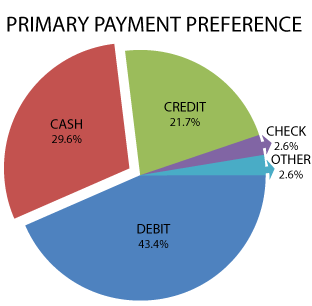

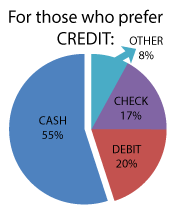

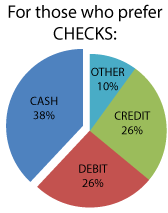

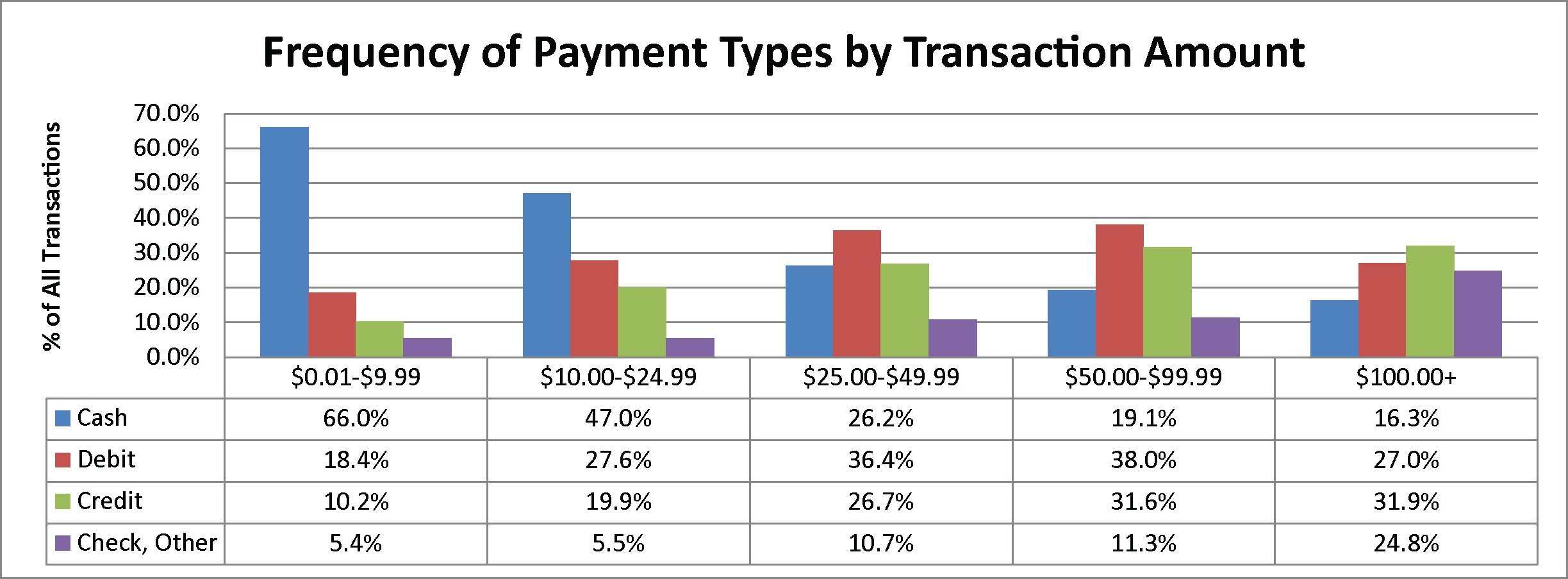

According to research from the Diary of Consumer Payment Choice that was conducted in October 2012 by the Boston, Richmond, and San Francisco Federal Reserve Banks, “consumers choose to use cash more frequently than any other payment instrument, including debit or credit cards.” In the diary, it was reported that the average American consumer conducted 59 transactions (51 in purchases and 8 in bill payments) per month, with 23 of those 59 transactions involving cash.

It’s easy to see why cash is often preferred over other forms of payment. Cash:

- plays a dominant role for small-value transactions

- stands as the key alternative when other payment options are not available

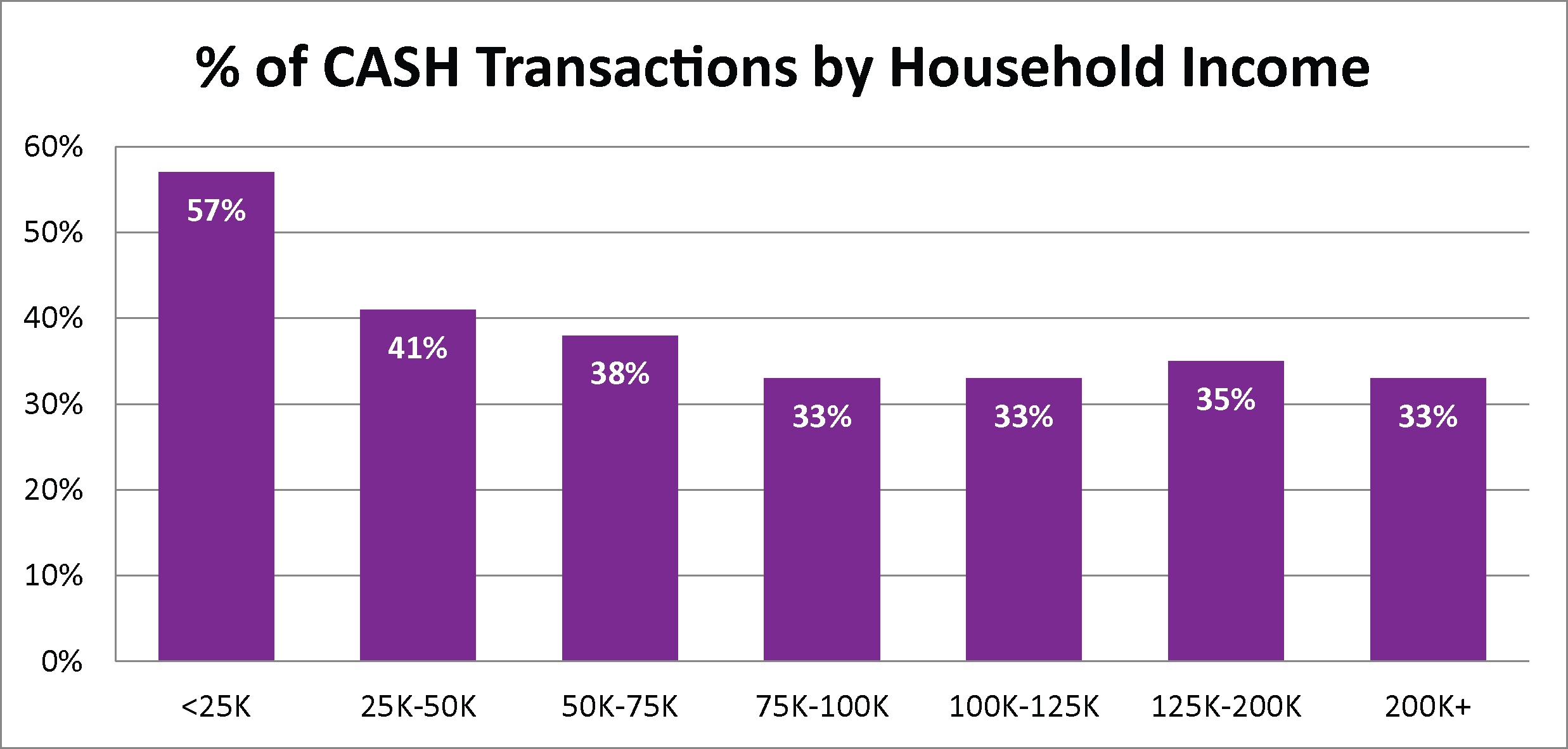

- is used for relatively larger-value transactions by mostly lower-income consumers who lack access to alternative payment options and/or find alternative payment options too costly or difficult to obtain

Money Fact:“[C]onsumers use cash for half of all their transactions valued at less than $50.”

– Diary of Consumer Payment Choice

Although payment with cash peters out once the transaction amount goes over $50, the average person makes only 9 non-bill transactions per month over $50 – compare that to the 42 non-bill transactions under $50 the average person makes per month.

Even though a heavy dependence on cash is commonly associated with a low-income household, no matter how much money a household makes, cash is still used for about 33% of all transactions.

To sum up, cash is and will remain the most dependable form of payment because:

- Different income and age groups use cash with almost equal frequency

- Low-value transactions, especially those under $10, are easily made with cash

- Everyday expenditures, like expenditures for food and personal care items, are often made with cash

- Cash is the main back-up payment instrument, especially in person-to-person transactions

- Lower-income households find other payment options too costly or too difficult to obtain

As long as cash remains the most widely accepted form of payment, counterfeit cash will continue to be manufactured and used.

How to Prevent Counterfeit Money from Affecting Your Business

For the larger businesses, counterfeit cash probably doesn’t take as large a bite out of the bottom line as other types of fraud. However, for small businesses, just one incident of counterfeit cash can cripple the business’s financial stability.

“For some merchants, like Target or Best Buy, the fake $100 bills are just the cost of doing business. But for some small businesses, hoping holiday season sales will help balance a slow year, a few phony notes can ruin the bottom line . . . When somebody realizes they can use it, they come back the next day and the next day”

– Julia Strzesieski, marketing director for Cole Hardware

When a counterfeit bill passes through a business, not only is the business out of the products ‘sold’ during the transactions, but also do not get the ‘profit’ from the cash that was used during the transaction and are also out any change they had given the counterfeiter during the transaction. Unlike payment cards, cash does not carry protection from fraud – meaning that neither the bank nor the police will reimburse businesses for counterfeit money that is discovered and turned in. According to Charlie White, an assistant special agent in charge of the San Francisco Secret Service office, “It is hard for small business[es] . . . It is mostly up to merchants to protect themselves, because the government doesn’t reimburse them for accidentally accepting fake money.”

So, then, how exactly can merchants protect themselves from counterfeit cash? Simple. Counterfeit Detectors.

In the past, counterfeit cash was able to be detected through the simple use of a counterfeit pen. The pen detected starch that was found in commercial papers; the paper used in currency was cotton and contained no starch. This pen has now become completely obsolete due to criminals bypassing the pen’s detection capability by spraying counterfeit bills with hairspray and/or using cotton paper to print counterfeit bills.

Counterfeit detectors, on the other hand, are machines that use a variety of different security measures to check whether or not a bill in question in real or fake. Take, for example, the CT-550 counterfeit detector scanner, that is used by retailers such as Macy’s, Ross, and Forever 21. This machine conducts an infrared scan, a magnetic scan, a portrait pattern recognition scan, and a paper quality thickness diagnostic, among other security checks, in order to determine if a bill is real or fake.

It is so incredibly important that businesses become as educated as possible about counterfeit bills and how to detect them – your loss prevention strategy is the only defense you have against counterfeit cash. Criminals are smart enough to know that by the time their counterfeit cash from a transaction reaches the bank, they’ll be long gone. Knowing this, the goal of most criminals is not to fool machines designed to detect counterfeits, but to fool the general public – in other words, the cashier at the register.

“A perfect reproduction is not the goal . . . [counterfeiters] aren’t interested in producing near-perfect notes that will get past bank checking machines . . . They just aim for something that’s good enough to fool the general public.”

– Allister McCullum, former counterfeit expert at the European Central Bank

.png)