Like most millennials, if you left college tens of thousands of dollars in debt with looming unemployment/underemployment on the horizon, there’s a good chance that you’ve done some unsavory activities, legal or illegal, that still brings about that tickle of regret and embarrassment in your stomach whenever you think about what you had to do to make ends meet. Of course, this is not to excuse the behavior of the man this post is going to be about, but rather, to highlight the fact that the cyber criminals stealing your identity and emptying your bank account are not sophisticated, Juilian Assange-esqe hackers: they are underemployed twenty-something year olds sitting at the kitchen table in their underwear and drinking a beer, using just a laptop and telephone to defraud some of the world’s largest financial institutions and their clients.

In 2004, 19 year old Belarusian Dmitry Naskovets was fresh out of college and working at a state-owned bank, when he joined a political demonstration against the president of Belarus and was detained by state security agents. Agents badgered Naskovets to give up his fellow co-conspirators, but he refused - even going so far as to not answer his phone when they called. The agents then began to call his place of work - the bank - which refused to renew his employment contract when learning of his after-work activities. After a difficult search for another job, Naskovets found work at an adhesive tape factory, where agents once again began to inconvenience his employer. Naskovets, again, found himself out of a job.

Naskovets had finally found a position at a car dealership when, in late 2006, a chance encounter on the subway with former schoolmate Sergey Semashko set in motion the events that would eventually lead to him working the graveyard kitchen shift at the rate of 20¢/hour at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn.

Semashko knew that for nine years in his youth, Naskovets had attended a public school with a demanding English program that held classes six times a week, giving Naskovets a noteworthy command of the English language. The chance encounter was quite fortuitous for both parties: Semashko had a job opening that required English fluency and Naskovets was feeling incredibly unsatisfied being a car salesman. Semashko told Naskovets to meet him at his apartment in a few days to discuss the job further.

Much to Naskovets surprise, Semashko - who wasn’t known to be rich - lived in an expensive apartment in a wealthy Minsk neighborhood. Without telling Naskovets much more than the fact that the job required a headset and an Internet connection, Semashko gave him $500 for simply meeting up with him. Naskovets didn’t need more incentive after that to take the job, no matter how ambiguous and unscrupulous the job seemed; $500 was more than he made at the car dealership in a month.

Per Semashko’s instructions, Naskovets created an email account where he could receive instructions from clients who had tasks that required a working knowledge of English. At first, Naskovets was instructed to perform seemingly innocuous tasks, such as checking the balance on a credit card or changing billing addresses. Rather quickly, however, the main activity for which he was needed was obviously illegal and in the realm of identity theft: impersonating bank customers in order to approve fraudulent transactions.

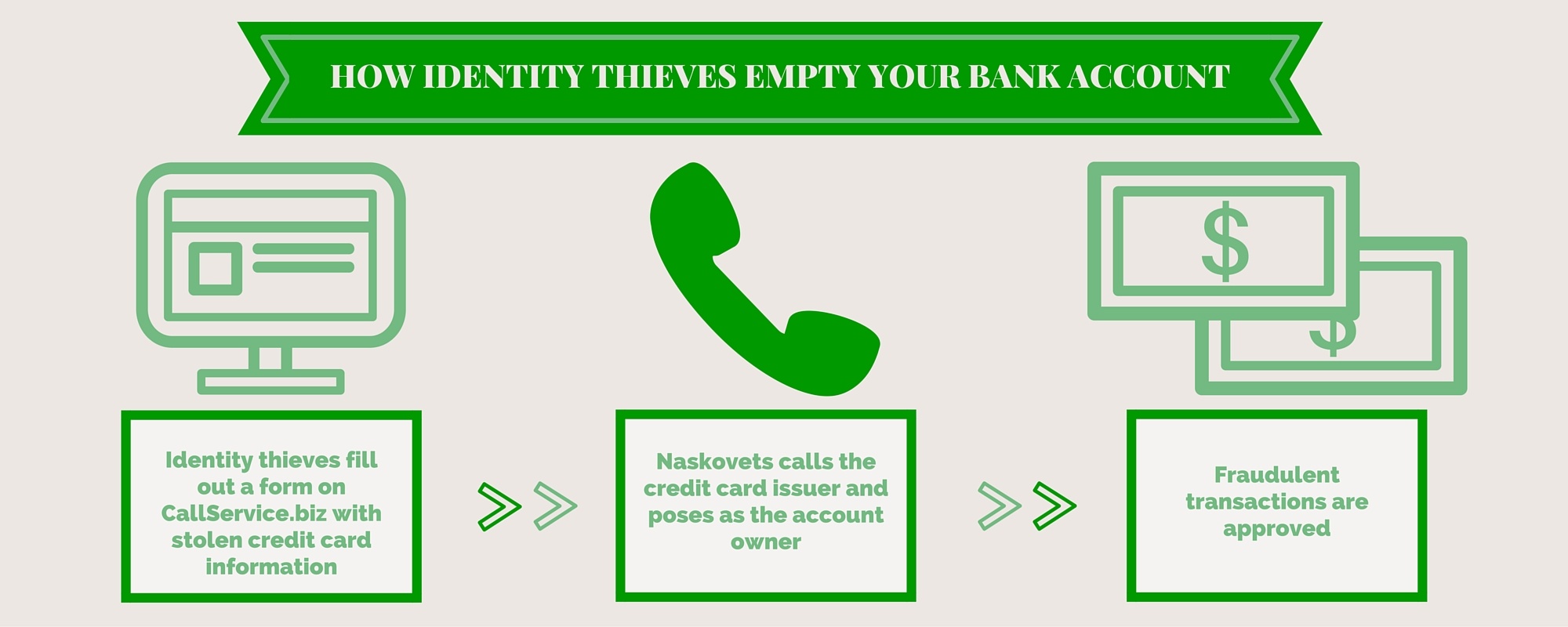

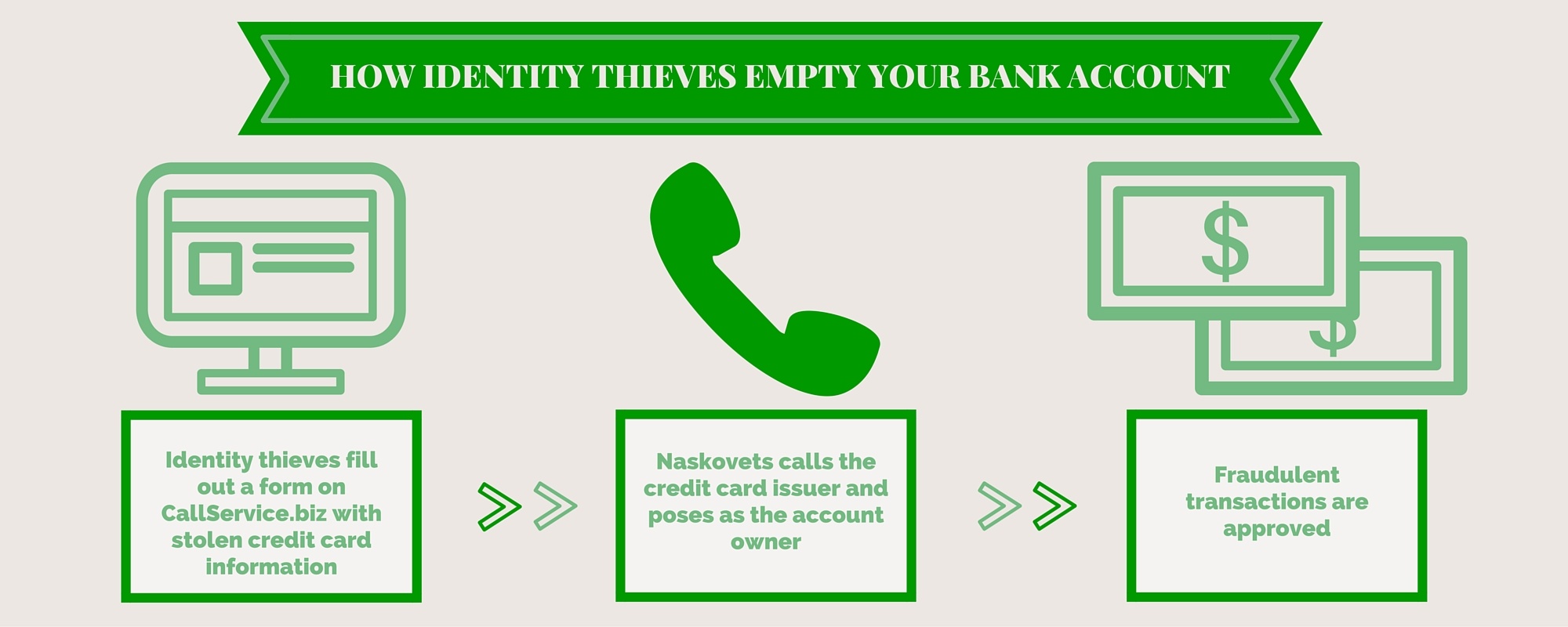

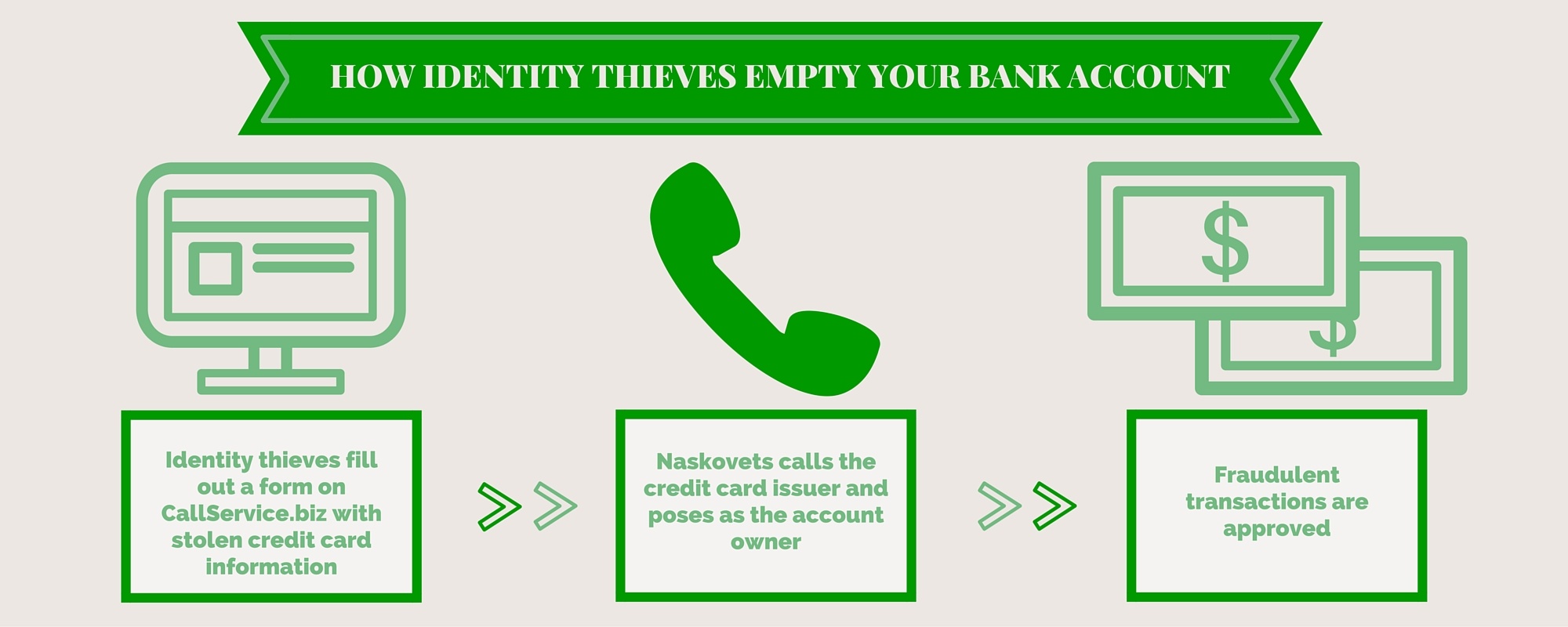

The way Semashko and Naskovets’ operation worked was quite simple: clients, who were already in possession of stolen credit card data – such as card numbers, billing addresses, and the answers to security questions (for example, “What is your mother’s maiden name?”) – would ask Naskovets to use that data to perform fraudulent transactions. For a fee, Naskovets would call the financial institution that issued the credit card and attempt to correctly answer the security questions as given by the financial institution’s representative who answered the call. Once all the correct answers were given, Naskovets was then able to conduct fraudulent withdrawals, transfers, and any other financial transactions that were requested by his clients.

Within six months, Semashko and Naskovets were so popular as identity theft facilitators that they found the need to create and advertise a website, CallService.biz, so that clients from all over the world could simply fill out a form with their requests, efficiently expediting the whole operation.

Although what Naskovets was doing was rather straightforward and uncomplicated, he was greatly sought-after for a reason: in this day and age, thanks to massive data breaches that occur far too often, stolen credit card data can be purchased on the dark web for as little as 50¢. But putting the stolen credit card information to use can be a problem for a good number of criminals. Most stolen credit card data ends up in the hands of foreign criminals who, despite their all their knowledge of how to get credit card data, are actually unable to use the credit card data due to their inability to speak English fluently. Often, the last step in successfully committing fraud via identity theft is talking to a bank representative to prove a person’s identity. This is where Naskovets would come into the picture.

With each fraudulent transaction, Naskovets fine-tuned his business formula to be prepared for any situation. He got in touch with another criminal who was able to churn out a fake ID in about seven minutes in .pdf format so that Naskovets could email to banks if they asked for ID. If he didn’t know the answer to a security question or if a bank representative got suspicious, feigning frustration and impatience was often enough to get the representative worried about their customer service rating that they would be willing to sidestep the security question or brush of their initial suspicions.

Naskovets was so good at what he did that he one time got a bank representative to authenticate his identity even though the bank representative had the actual owner of the credit card in question on the other line! Naskovets simply answered the security questions to the bank representative’s satisfaction than the actual owner could. It’s actually not that difficult or shocking to see how this could have happened: answering a question as simple as “What is your favorite movie?” can be problematic since most people’s favorite movie changes as they get older. The actual owner of the credit card has to remember the answers to security questions off the top of his head, while Naskovets effortlessly reads the answers off his computer screen.

This isn’t to say that every transaction went off without a hitch: there was an instance when Naskovets had to impersonate someone named “Thomas Jefferson”, but the bank representative became suspicious when it was apparent Naskovets was unaware about the namesake.

Naskovets would make up to 30 calls to financial institutions per day and either charge $20 per phone call or a percentage of the total transaction. He could make as little as nothing a day or as much as $1,000 a day, but making enough to go to nice restaurants, go to nightclubs, and travel the world. According to Naskovets, “It was a good life…The most important thing was a kind of freedom from anything.”

By 2009, Naskovets had married and was actively trying to put his cyber-criminal days behind him. With the money he had saved up from his fraudulent activities, he moved to Prague with his wife with plans to open a pet supply store. However, clients kept on messaging him with requests, and with such a lucrative business model, he just couldn’t seem to get out of the life completely.

On April 15, 2010, Naskovets was in his Prague apartment when the power suddenly cut out. When a man in an orange jacket knocked on his door, Naskovets assumed he was the electrician sent to fix the outage, and opened the door. Of course, this man was not an electrician, but a Czech law enforcement agent. Naskovets was just one piece of an international sting operation headed by the FBI that day: Belarusian authorities arrested Semashko and other co-conspirators in Belarus, Lithuanian authorities seized computers in Lithuania that hosted CallService.biz, and the FBI took control over the CallService.biz domain name.

Following his lawyer’s advice, Naskovets agreed to be extradited to the United States on September 20, 2010, and was placed in Brooklyn’s Metropolitan Detention Center. After pleading guilty on February 23, 2011 to charges of conspiracy to commit wire and credit card fraud, Naskovets was sentenced on March 23, 2012 to 33 months in prison, three years of probation, and $200 in fines.

According to CallService.biz advertisements as found by the FBI, Naskovets and Semashko’s business had helped over 2,000 cyber criminals commit over 5,000 fraudulent transactions. However, authorities were only able to produce enough evidence for three counts on his indictment: one count of conspiracy to commit wire fraud, one count of conspiracy to commit access device fraud, and one count of aggravated identity theft.

In September of 2012, Naskovets was released from jail – due to time already served and good behavior – only to be subject to a deportation order to send him back to Belarus and potential torture. After petitioning the Immigration and Customs Enforcement court to let him remain in the United States under the U.N. Convention Against Torture on which the United States was a signatory, he was granted his petition in October 2014.

Whether or not one may be inclined to believe him, Naskovets seems set on rectifying the errors of his past: he reached out to American Expres - a frequent target of Naskovets' fraudulent activities - to offer his help in fixing the flaws in their security protocols, but they didn't accept his offer to help. In addition, in early 2015, Arkady Bukh, the lawyer who represented him during his criminal case, and he created CyberSec, a cyber-security firm dedicated to using hackers’ knowledge of computers to do good.

.png)