We have talked much in previous posts about the intricacies of money laundering, and the dangers those pose from a national security standpoint. Organized crime groups such as South American drug cartels launder the proceeds from their drug sales to hide the money’s illicit origins and profit from the dangerous trade. Less mentioned was the post-2001 addendum to many money laundering regulations. The “TF” in MLTF, which stands for “terrorist financing” is the best indication of the alarming frequency with which terrorist groups are also turning to money laundering to finance their operations - and taking American business down with them.

A recent report from the U.S. government about the Lebanese group Hezbollah highlights that connection. Canada, Australia and the Netherlands consider the group, in whole or in part, a terrorist organization, and the U.S. State Department placed the group on its official list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations in 1999. Hezbollah has been linked to a series of bombings and kidnappings in the 80s and 90s -- they are, to put it mildly, very bad guys. And recently they turned away from their traditional sources of financing and to drug and money laundering through American-based businesses.

We know this because last February, after a thorough investigation, the U.S. accused a Beirut bank of facilitating much of the money laundering operations. Under the provisions of the PATRIOT Act, American financial institutions and organizations were forbidden from any business dealings with the bank, named the “Lebanese-Canadian Bank”, which caused it to quickly fold. Its books were then seized and opened, in preparation for a sale of its remaining assets. The result was an insightful glimpse into the shady underworld that crossed terrorist financiers with unscrupulous bank officials and South American drug-runners.

We know this because last February, after a thorough investigation, the U.S. accused a Beirut bank of facilitating much of the money laundering operations. Under the provisions of the PATRIOT Act, American financial institutions and organizations were forbidden from any business dealings with the bank, named the “Lebanese-Canadian Bank”, which caused it to quickly fold. Its books were then seized and opened, in preparation for a sale of its remaining assets. The result was an insightful glimpse into the shady underworld that crossed terrorist financiers with unscrupulous bank officials and South American drug-runners.

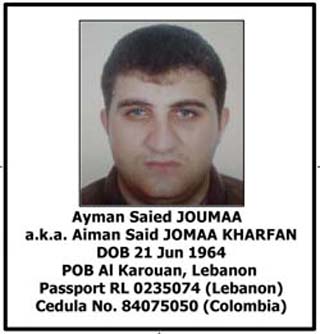

A central player facilitating the trade was Ayman Joumaa, a Lebanese-born businessman residing Colombia, with ties to Hezbollah and the notorious Los Zetas drug cartel. According to the US indictment, Joumaa was the middleman in a vast drug trafficking operation, taking cocaine produced in Colombia and South America, and shipping it to Africa and Europe. Proceeds from these sales would be laundered through various enterprises in the United States, before coming back to the cartels.

Drug Enforcement Administration documents reveal common techniques used by Joumaa and his partners to launder their drug money. One cited case involved used-car dealerships: cars would be purchased with drug ostensibly for resale in Africa, and the payments deposited into Beirut-based money-exchange houses owned by Joumaa, mixed in along with proceeds from the drug trade. The Beirut bank houses are notoriously secretive, but even so investigators discovered a lot more money was coming in than what could be accounted by car sales alone.

In this particular case, the dealership businesses were willing partners to Hezbollah. One could easily imagine a less appealing case - a small or medium-sized business falling unwitting victim to the drug-money launderers, and shut down as a result of a U.S. government investigation. There is the is the most compelling reason to use strict identity-verification procedures. Ensuring accounts are not set up in benefit of nefarious international organizations is the best way to keep business free from entaglement of U.S anti-terrorism laws - which, as Joumaa and his U.S. financiers learned, carries some severe penalties.