Shortly after the terrorist attacks of 2001, an Islamic terrorist cell in the U.S. sprang into a different kind of terrorist activity. The mastermind of the group sat down in front of a computer and sent out emails.

A lot of emails, actually, laden with malicious trojan programs embedded in innocuous emails, that can take control of unwitting users' computers resulting to identity theft. Other emails spoofed emails from reputable on-line stores like eBay, complete with links to imitation login pages, asking users to “verify” their credit card accounts.

Much of the money stolen from these accounts, about $3.5 million in total, made its way back to Waseem Mughal, Younis Tsouli and Tariq al-Daour, the trio of terrorists who used them to purchase provisions for their jihadi brethren in the Middle East. Their shopping lists included night vision goggles, cellphones, GPS equipment and various other items to ship overseas. They also bought airline tickets – more than “250 … using 110 different credit cards at 46 airlines and travel agencies” according to a Washington Post investigation.

The group did not stop there – leftover cash was laundered through gambling websites. A few of the big ones mentioned in WaPo article include Betfair.com and AbsolutePoker.com. Al-Daour, possibly the most technically-savvy of the group, placed bets with the websites using the stolen accounts from their identity fraud, and collected whatever winnings they got into their own bank accounts.

While the UK's Scotland Yard was fortunate enough to discover the group and arrest them before they could realize their deadly plans (and not a moment too soon – a search of their property immediately following their arrest uncovered a large stash of explosives), the larger danger of terrorist financing through money laundering remains.

Terrorist financing, especially as it intersects money laundering, has in fact been a point of concern for the U.S. and international government long before the terrorists attacks in New York. Legislation criminalizing the act has been around at least since the 1970s, but never in the same focus as it came to be after September 11th, 2001. A rash of new laws, with overlapping, and sometimes contradictory provisions were passed by the UN, the EU, Britain and US. Congressional testimony by government-appointed counter-terrorism officials kept repeating the same findings: terrorist financing is at the same time pervasive and opaque; finding it is and will remain the primary challenge for law and enforcement and national-security organizations.

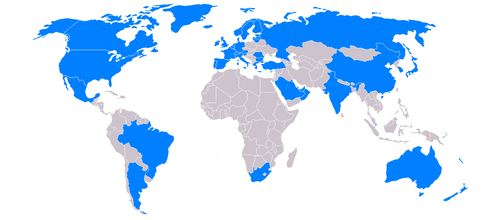

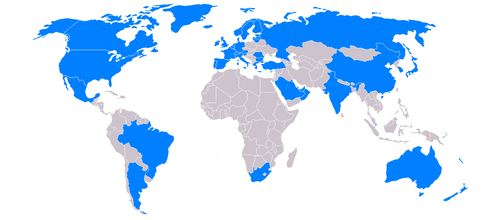

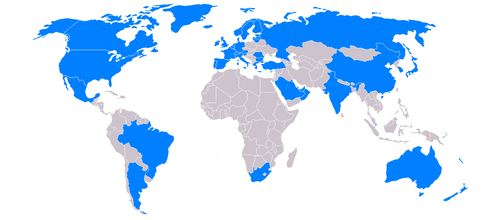

![Money laundering finances terrorist organizations worldwide (Image: By Masterdeis (Own work) [GFDL (www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)](https://blog.fraudfighter.com/hs-fs/file-15539862-png/images/500px-fatf-gafi_map.png?width=386&height=170&name=500px-fatf-gafi_map.png)

The cornerstone law, and the first sweeping change came just weeks after the attacks, when the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1373, which called for greater cooperation in combating terrorism, and specifically for member states to take “additional measures to prevent and suppress, in their territories through all lawful means, the financing and preparation of any acts of terrorism”, in addition to criminalizing terrorist fund-raising and freezing funds of known terrorists individuals or organizations.

Within the United States, almost every important government agency was mobilized in some way to detect and disrupt terrorist financing. Especially important was Title III of the USA Patriot Act (which we discussed in our previous post on “Know Your Customer” regulation), called the “International Money Laundering Abatement and Financial Anti-Terrorism Act of 2001”, parts of which provided for the establishing of “internal policies, procedures, and controls” to control money laundering, along with an employee training program and an audit mechanism.

We have been tracking this legislation since its inception, and continue to develop solutions such as identity theft protection to make compliance around with these laws as simple and cost-effective as possible. In our next post, we will go into detail on a key section of the act, which requires identity verification, and provide an easy compliance solution you can implement in your organization.