We have mentioned in our previous posts that

fraud committed on a stolen credit card affects three different parties: the consumer whose credit was used in committing the crime, the financial institutions handling the payments, and the merchants where the fraudulent buy took place. Out of the three, consumers lose the least; mainly because zero-liability laws guarantee to restore their losses. Those same laws then leave financial institutions and merchants to divide up the bulk of the losses. We will focus in this post on FIs, gauging the effectiveness of their current fraud mitigation techniques, and suggesting areas in which their efforts can be improved

In addition to losses from customer attrition, which we discussed here, FIs face around $11 billion annually in hard losses from fraud. This includes not only write-offs from fraudulent purchases, but also some significant fees and costs in processing disputes and resolving the issue with both vendor and consumer. For instance, reversing the charge on a buyer's account often means a fee to the card association. Verifying the charge with a signed sales draft from the merchant entails a separate fee. And the coordination between issuing banks, acquiring banks, merchants and buyers in resolving the fraud dispute calls for considerable expense and man-hours of work.

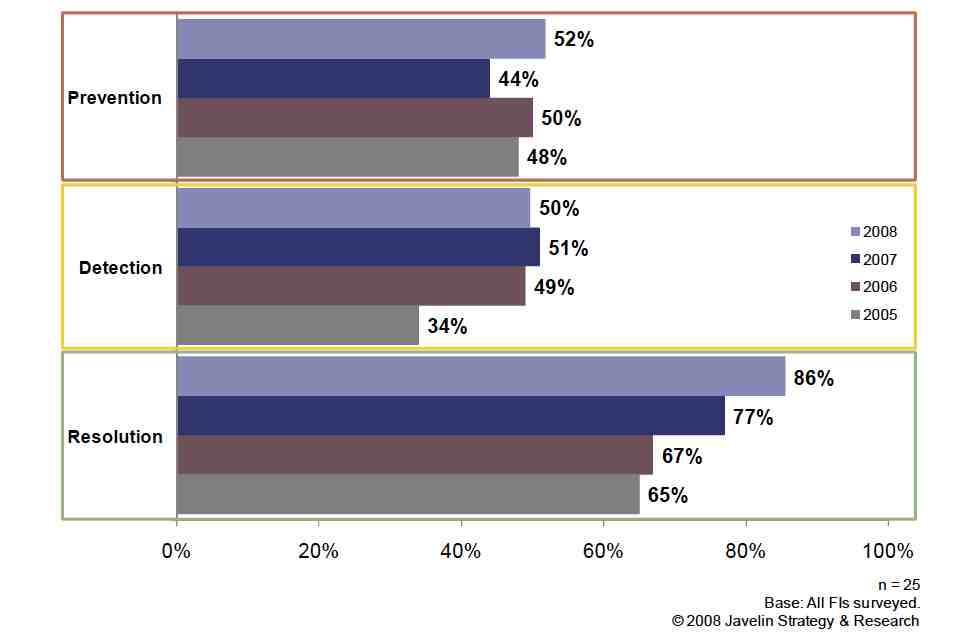

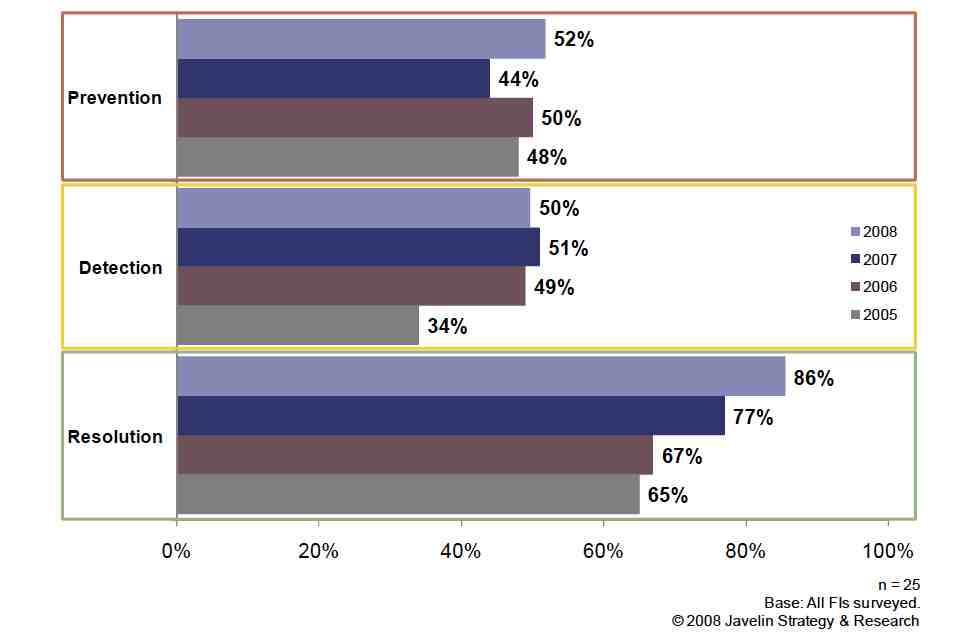

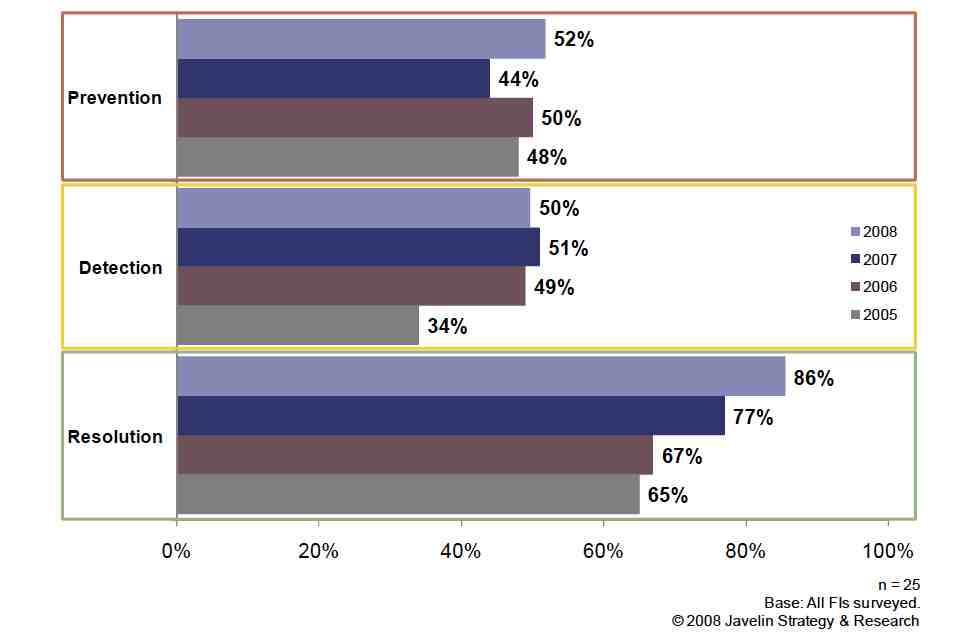

The Lexis-Nexis and Javelin Research survey of financial institutions' ability to handle identity fraud found that since 2005, the sole area of progress has come in resolution. Advanced software algorithms can better sniff out out-of-place purchases and notify the cardholder of likely fraud -- undoubtedly improving cardholder satisfaction, but since it does not deal with these purchases until after the transaction is complete, this does very little to help keep financial losses down.

Conversely,efforts in stopping fraud at the point of sale in recent years have been at a standstill: Javelin's patented test of financial institution “Fraud Prevention, Detection and Resolution” capabilities found that only around half meet its “Safety Score-card Criteria” in the Prevention and Detection standards laid out in the test. In other words, while FIs have indisputably improved in refunding victims for fraudulent purchases (the Resolution part), they have progressed little at improving their capabilities of stopping the fraud at the point of sale (the Detection and Prevention). The 45% - 50% proportion of FIs meeting Javelin's fraud safety standard has hardly moved for the last several years, meaning fraud losses are eating away an ever-increasing chunk of financial institution profits.

The risk is compounded by card-issuer giants Visa, MasterCard and American Express, who have historically been reluctant to impose, or for that matter tolerate, what they have deemed burdensome measures protecting merchants and financial institutions from point-of-sale card fraud. Both Visa and MasterCard, for example, prohibit merchants accepting their branded cards from requesting additional “Cardholder Identification” beyond the valid, signed credit card, and refusing a sale based solely on the lack of that identification.

It is our position that this thinking is outdated, and a new paradigm in thinking is needed. Merchants who are willing to enforce identity checking during the credit transaction ought to be given preferential rates and rewarded with rebates and bonuses when they achieve significant fraud reduction thresholds. The simple process of asking to view the ID of the person using the credit card and visually comparing the name on the ID to the name on the card should produce significant reduction.

Taken a step further, this strategy can virtually eliminate physical credit card altogether. Verify that the ID is REAL and that the name on the ID matches the name on the credit card, and the odds of a fraudulent transaction occurring must fall to extraordinarily low levels compared to what is currently the case.