Sharp Spike in Fraudulent Tax Returns Reported by IRS

The "first lady" of tax-refund fraud is Rashia Wilson (posing with the loot on her Facebook page, above) who, along with her co-conspirators, claimed false rebates of more than $11m.

In 2013, more than 12.6 million Americans will have their identities stolen. That's one every 3 seconds.

The FBI reports that medical fraud last year totalled "somewhere betwen $70Billion to $240Billion". The mere fact that the estimated losses display such a wide range of possible values gives testament to the difficulty of tracking and preventing this type of fraud.

It is not necessary to be advanced in computer science, nor to have impressive hacking skills in order to steal personal data. Names, addresses and Social Security numbers can be stolen from doctor’s offices, nursing homes and hospitals. Usually an insider is involved. Medical assistants, or billing clerks have access to vital personal patient information. Other times, outsiders may perpetrate the theft of stolen information by distracting secretaries in order to grab patient files. Fraudsters commonly obtain information from their victims over the phone by posing as, say, Medicare reps. Others may use the identities of dead people after searching genealogical or family-support websites. The Affordable Care Act is a gift: complaints about phone calls and visits from bogus Obamacare “navigators” are on the rise.

A popular target for identity thieves is tax-refund fraud. The scope for abuse of the Federal and State Tax-Return processes is immense due to the large-scale volume tax-returns: 145 million individual income-tax returns were filed for fiscal 2012 in America, of which up-to three-quarters were entitled to a rebate. Using stolen personal details and made-up withholding forms, a fraudster can apply online for dozens of refunds a day, to be sent to addresses of his choosing. When the real taxpayer tries to file a return (assuming he’s alive), the IRS rejects it, and the mess can take months to sort out. So common is this scam that it has its own acronym, SIRF (for Stolen Identity Refund Fraud).

Some criminals who have been prosecuted for this activity admit to working on an industrial scale, putting in 12-hour days with a dozen or more accomplices, each filing multiple tax returns per day on laptops. Street gangs have been reportedly moving from drugs to refund fraud because it is more lucrative, less physically dangerous and, in some states, much less harshly punished. The epidemic has been seen to spread even to the prison system. The IRS caught more than 170,000 suspicious refund applications from inmates between January and September of last year. How many slipped through the net is anyone’s guess.

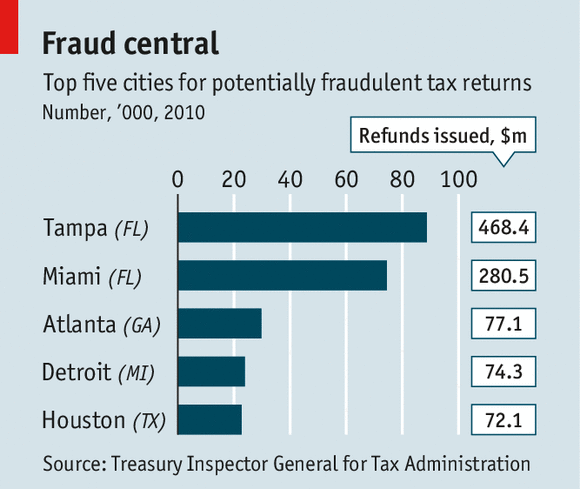

Florida has the highest rate of ID theft, and its joint capitals are Miami and Tampa

(see table). Fake returns in and around Miami are more than 40 times the national average. A number of factors make the state vulnerable to such scams, among them its crowds of pensioners, large numbers of immigrants with poor English (who can be more easily duped into disclosing personal information) and its high rate of people who do not have to file tax returns (meaning more stolen numbers can be used without detection, because they do not generate duplicate filings). So many people stopped by Tampa police in 2011 were found to have lists of stolen IDs on them that the city’s exasperated mayor, Bob Buckhorn, declared the IRS “missing in action”.

(see table). Fake returns in and around Miami are more than 40 times the national average. A number of factors make the state vulnerable to such scams, among them its crowds of pensioners, large numbers of immigrants with poor English (who can be more easily duped into disclosing personal information) and its high rate of people who do not have to file tax returns (meaning more stolen numbers can be used without detection, because they do not generate duplicate filings). So many people stopped by Tampa police in 2011 were found to have lists of stolen IDs on them that the city’s exasperated mayor, Bob Buckhorn, declared the IRS “missing in action”.

A report by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration found the agency might have sent out 1.5m potentially fraudulent refunds in 2011, including 655 to a single address in Lithuania. (In 2010, almost 4,900 refunds were sent went to just five American addresses.) The IRS insists it is getting to grips with the problem. It has doubled the number of employees working full-time on ID theft to 3,000, even as its budget has been cut. This has helped reduce the average time it takes to resolve cases from ten months to four, and has raised the amount of fake refunds that are blocked before being sent out to $20 billion in the 2012 tax cycle, from $14 billion the year before. The IRS could cut losses further if it were able to delay posting refund cheques until it had time to cross-check them against income data from employers, which it receives weeks later. But that would require an act of Congress, and there is little political support for making people wait longer for their money.